Autism Causes

Since its official identification in the 1940s, autism research shows no single cause for autism. Research tilts towards a combination of contributory factors;

- Genetic factors including genetic mutations report to be highly determining of autism at 80%.

- Environmental factors including toxins, infections, stress, child traumatic birth injuries or infections.

Autism Treatments

What Does Autism Look Like?

Autism has no obvious look, meaning one cannot know that someone has autism just by looking at them! With traditional physical disabilities that are easier to identify, many people want to physically see “autism”. More often than not, people say “but he or she does not like!” Because autism by nature is NOT like other obvious disabilities that are easily observed. Autism requires understanding of its presentation and interaction with a person for one to identify.

The reason people cannot see autism is because autism deficits are in the brain, which we all cannot see but infer from interactions by specifically recognising difficulties in social communication and behaviors. The individual with autism will exhibit behaviors that substantially deviate from normative ways of behaving shared by majority of the people. Autism only becomes apparent when an individual is not in tune with societal expectations of behaving at given ages.

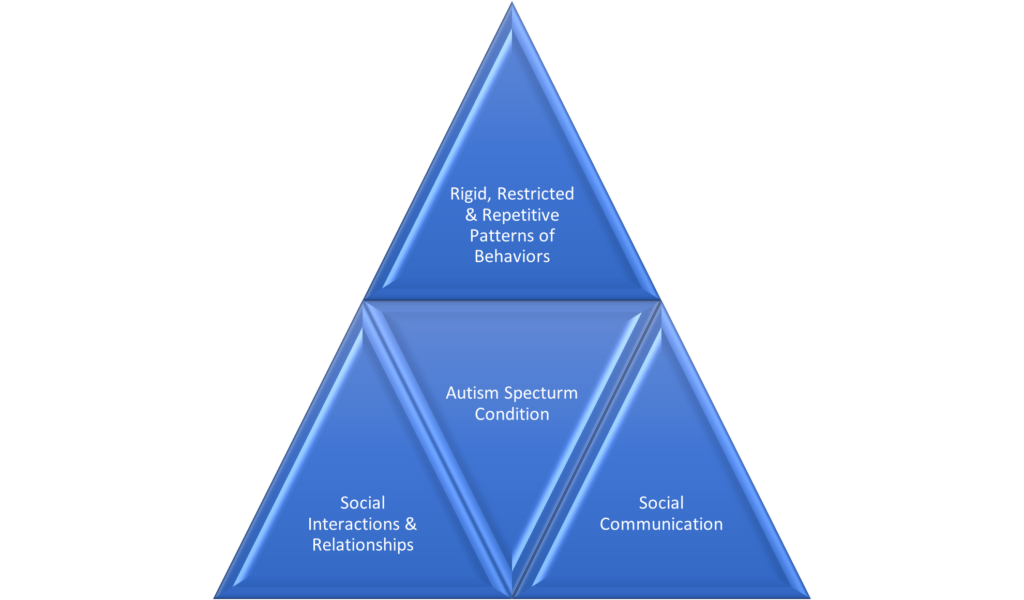

Autism presents a continuum of symptoms and behaviors reflecting varying degrees in relation to severity. The variations in the presentation of symptoms from person to person gives autism its “spectrum” name—each individual uniquely displays a triad of impairments as a result of autism.

A. Qualitative Impairment in Social Interaction and Relationships

The social nature endowed in humans is the most widely known challenge for people with Autism. Autism presents difficulties in adhering to rules and principles governing social interactions, primarily because of the way their brains perceive and process socially related information. As a result, people with autism can be more gullible and naive to social behavior and can be easier targets for teasing, bullying and victimization. Some of the impairments observed in social interactions and relationships include but not limited to the following;

- Social isolation and preference for lone play;

- Struggle with seeking out friends or friendships or joining in social exchanges.

- Lacking social awareness (behaving as if other people do not exist).

- Showing disinterest and dislike to engage in social behavior.

- Higher preference for objects than people.

- Lacks spontaneous shared enjoyment, interests and or achievements;

- No showing or pointing out objects.

- No showing or pointing out objects.

- Inability to take into account context, social cues and conventions;

- No give-and-take nature of conversations and relationships.

- Lacks turn-taking skills.

- No sharing of objects/toys with others.

- Does not ask for things.

- Does not wait for own turn.

- Lacks joint attention skills.

- Expresses aggression when own needs are not recognised or given

- Struggles negotiating socially.

- Inappropriate touching and closeness to others.

- Problems with social and emotional reciprocity and empathy.

- Emotions are not expressed according—mostly out of tune with reality.

- Difficulties to read or recognise emotions.

- Fails to attune to emotions.

B. Qualitative Impairments in Social Communication

- Communication is the centre of social life. In order for one to experience good quality and enjoyable life, it is necessary that needs are communicated and met. In the autism world, communication, specifically, lack or limited age-appropriate speech is common. This leads to presents as a great challenge and while looking to understand autism difficulties, parents and practitioners are, at the same time, navigating solutions to enhance ability to communicate. While young, people with autism can often speak fluently and appear to have “typical” expressive and receptive language, they usually present impairments in pragmatic language skills. Pragmatic language refers to the use of language in conversations and relationships. Generally, autism as a spectrum condition presents variant social communication competencies and difficulties. Examples of social communication impairments may include but not limited to the following;

- Common speech difficulties;

- Delay in, or total lack of, the development of spoken language (not accompanied by an attempt to compensate through alternative modes of communication such as gestures).

- Do not respond when name is called.

- Cry inappropriately or melt down when needs are not met.

- Gibberish vocalizations that are hard to make out.

- Lacks eye contact to initiate, terminate or regulate social communication.

- Lack of consistent facial expressions (in response to activity or emotions)

- Little or lack of communicative gesturing (pointing, hand movements)

- Difficulty in comprehending and following instructions.

- Continuously repeating words they have heard from others.

- Uneven development of language and speech skills (not at a typical level of ability, and unevenly)

- Unusual speech prosody (rhythm/intonation).

- Difficulties understanding implied meaning, interpret what is said literally.

- Struggle with general conversational rules;

- Inappropriately gaining and maintaining another’s attention.

- Swapping between listener and speaker role.

- Difficulties choosing and staying on topic.

- Getting lost in details and losing the point in an exchange.

- Pragmatic language difficulties include challenges;

- Not getting what was communicated when unsure.

- Behave like they understand what is communicated, when in fact they do not.

- Share difference of opinion.

- Want more information or clarification.

- Difficulties expressing thoughts, opinions, emotions or needs—may use physical means like kick, hit, scream to say that they are not happy.

C. Rigid, Restricted, Repetitive Patterns of Behaviors, Interests and Activities.

- Playing with objects/toys in a stereotyped manner.

- Stereotyped patterns of interest that is abnormal either in intensity or focus.

- Unusual play with objects;

- Spinning objects

- Sniffing foods and objects

- Lining up toys

- Categorising toys by color or patterns

- Fixed adherence to specific, non-functional routines or rituals.

- Putting on shoes (E.g. starting with the specific side of the foot even when the opposite is presented).

- Going to the same room to pick a toy or a book before starting the day.

- Rigid thinking patterns or preference for predictability, routine and consistency.

- Difficulties managing change or transitions between activities.

- Stereotyped and repetitive motor mannerisms (e.g., hand-flapping or twisting, observing own hand or fingers, complex body mannerisms, running in circles).

- Attachment to play objects—trampoline, swing, blanket, stuffed animal, cooking stick, spoon, shoe in

D. Additional difficulties observed in Autism

1. Sensory sensitivities

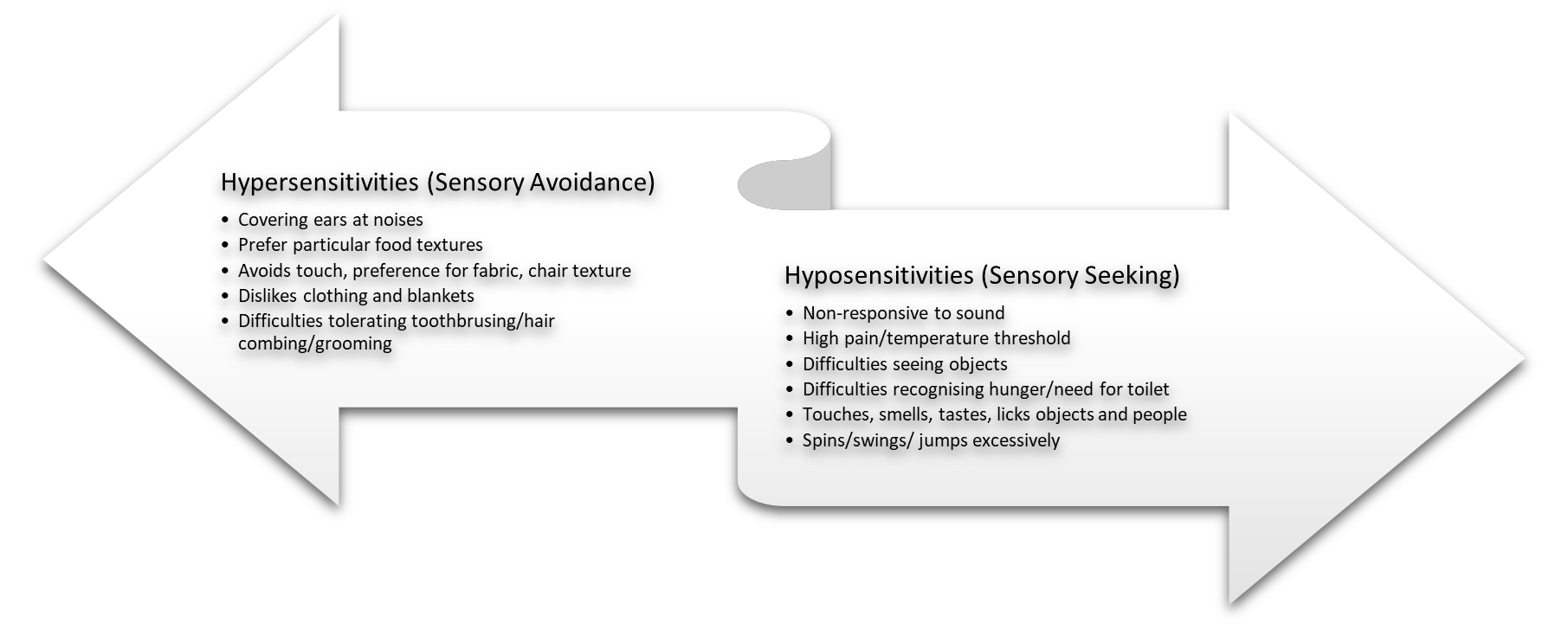

Hyper/Hypo sensitivities

Challenges with sensitivities come from sensory interaction with the environment and interpretation thereof. While these sensitivities fall on a continuum, many individuals with autism experience these on two extremes—hyper (overly) or hypo (low) sensitivity to sensory experiences. The hypersensitivities are often recognised as “sensory avoiders” require very light sensory stimulation in the senses to experience a reaction. Those with hyposensitivities, often referred to as “sensory seekers” may not react to sensory stimuli because it is poorly registered or recognised to elicit a reaction. Examples of hyper/hypo sensitivities may include but not limited to the following;

2. Fine and Gross Motor Difficulties

- Clumsiness and poor handwriting

- Problems with adaptive functioning

- Personal care and independent living skills

Theory of Mind

Theory of Mind (ToM) refers to the ability to put oneself in another’s shoes, literally taking their cognitive, emotional and visual perspective. This process equips children with skill for social interaction, group dynamics and behavior (Peterson, Slaughter, Peterson & Premack, 2013). For autism, the inability to appreciate the group perspective produces mind-blindness as a result, many people with autism experience difficulties understanding emotions, thoughts and intentions in themselves and others (Baron-Cohen, 1995). By adolescence, most individuals with Autism would pass a basic ToM test and are likely to be aware of the factual information known by another. However, they have difficulties to imagine the ways in which the other person perceives the factual information, or the emotions that they have in response to it. Major ways in which the Theory of Mind impairs social communication is illustrated in Figure 4 below:

3. Central Coherence

Central coherence (CC) is the ability to integrate pieces of information into a whole (Happe & Frith, 1996). With very weak central coherence, a person with Autism focuses on details without attending to the central meaning. Strong central coherence enables someone to comprehend and remember the gist of a conversation, story or situation and to integrate multiple cues to get a sense of the whole. Weak central coherence can impact the young person in a number of ways:

Weak central coherence

- If every detail is important, changes to the environment might be overwhelming.

- If someone remembers where everything is placed, moving things around maybe a source of distress.

- Challenges to integrating multiple stimuli might lead to difficulty noticing and responding to others’ emotions.

- If every detail is important, a change may result in something that has to be learned new, rather than being understood as something that is essentially similar

- The ability to generalise is difficult.

- Challenges attending to and integrating a range of types of cues, rather than the ‘whole’ of a social scene might lead to misinterpretation, faulty conclusions and eventual inappropriate solutions.

4. Executive Functioning

Executive functions (EF) refer to higher-order cognitive processes such as the ability to adapt behaviour to a changing situation, to plan and organise future behaviour, and to think abstractly. It is important to recognise that challenges in cognitive deficits are not permanent. Research shows that interventions in childhood, as well as family adaptation and individual compensatory strategies, make deficits less intrusive in adolescence. Below are executive function difficulties in autism;

- Planning and organisation

- Predicting ahead and planning to achieve a desired outcome, or avoid a pitfall.

- Concentrating, dividing attention, or shifting attention from one activity to another.

- Impulse control problems: knowing how to start and stop particular

- Getting started with a task or conversation.

- Reflecting on past experiences and adapting what has worked or did not

- Understanding the passage of time particularly trouble estimating time frames, losing track of time, prolonging a conversation topic or having particular expectations about start and end times for sessions.

- Adapting to new situations.